From hieroglyphics to clear labeling

Buying lumber can be a bewildering experience, especially if you’re trying to support Maine stewardship and Maine jobs with your choices.

Take the choice of two 2 x 4s pictured below. They were bought in the same lumber yard, on the same day, for the same price. One is produced by Maine landowners, loggers, truckers and mill workers. The other is not. Which is which?

Photos by Lee Burnett

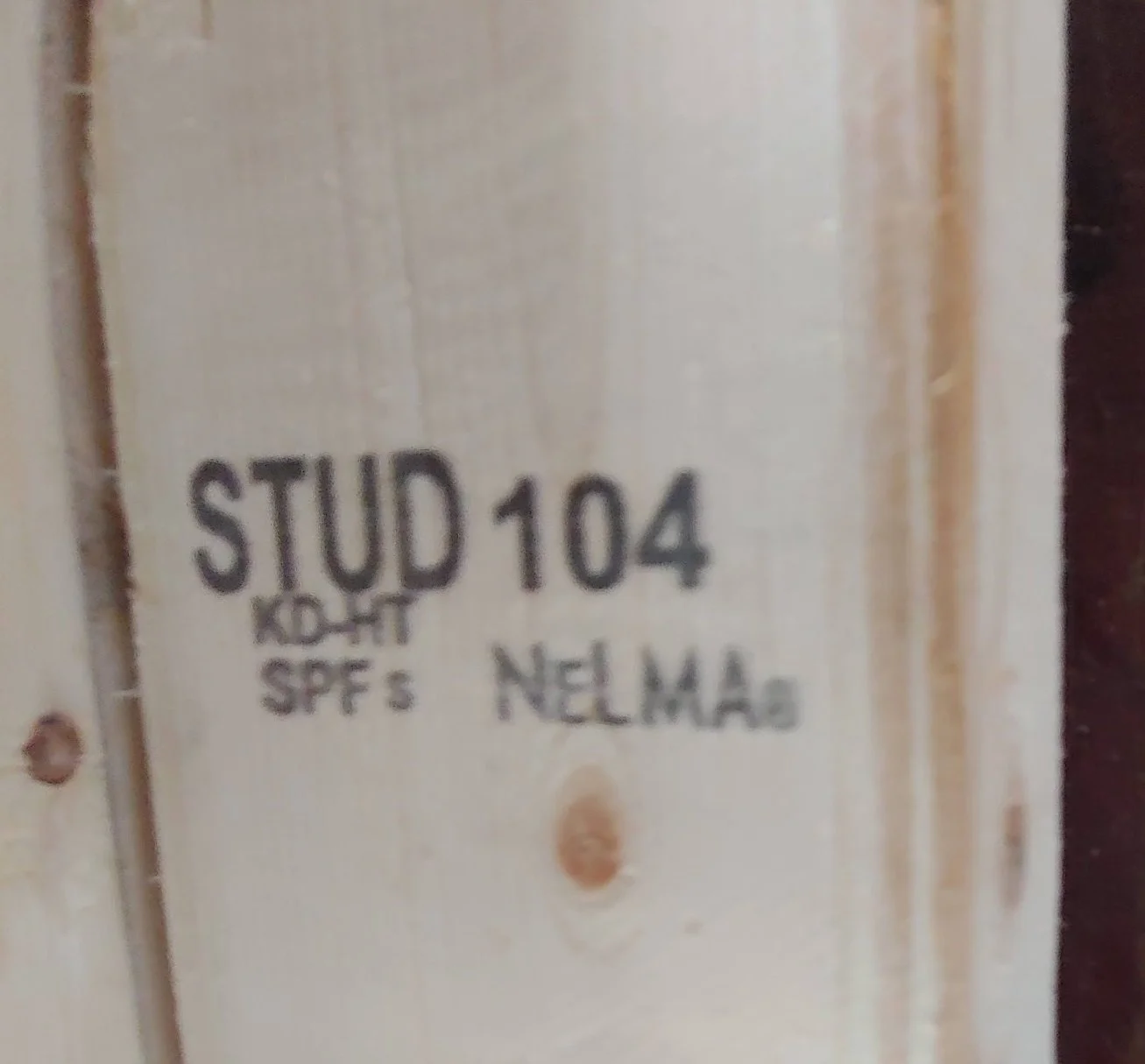

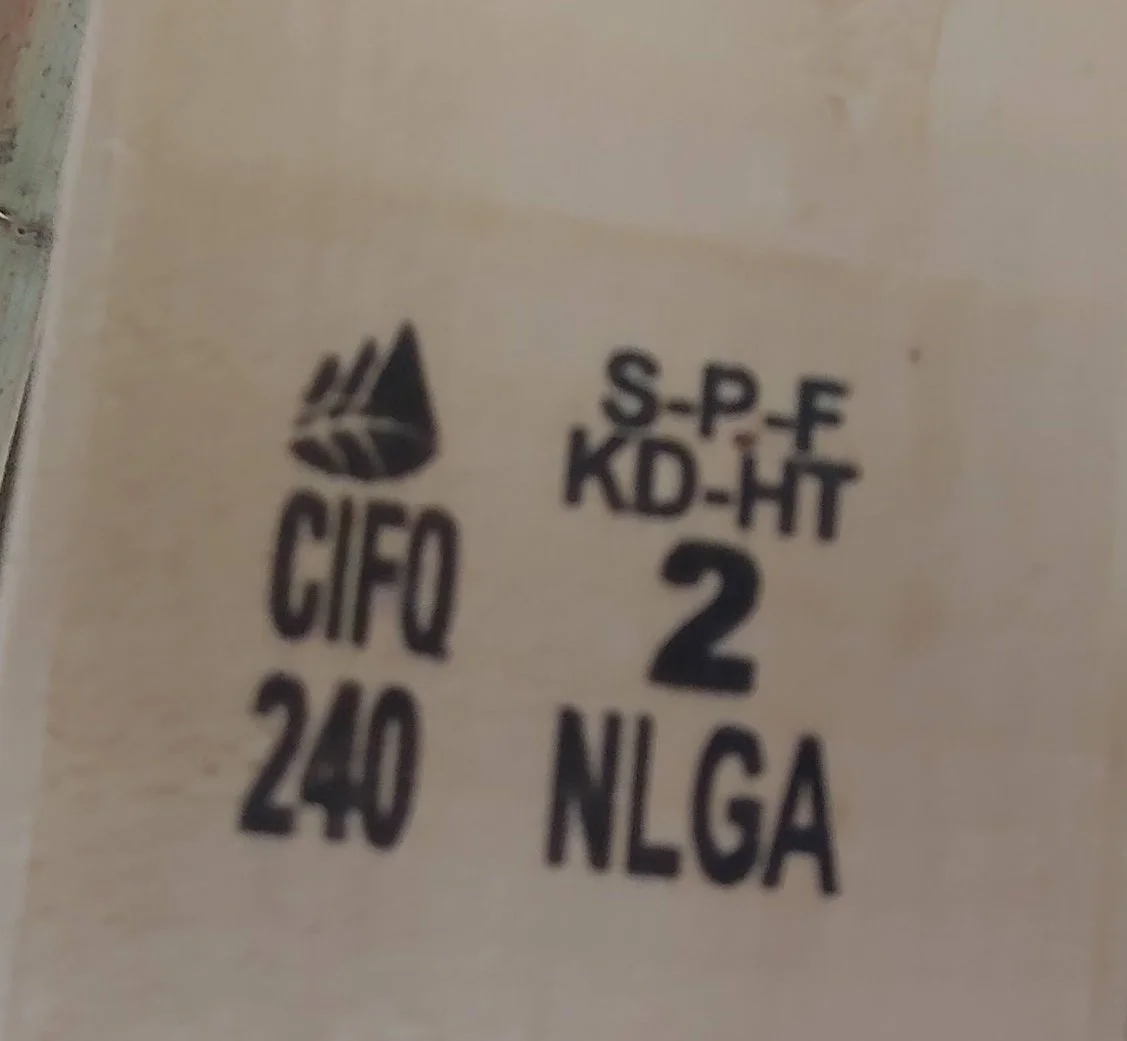

You have to know the hieroglyphics stamped on the side to make an informed choice. The wood stamped NeLMA refers to Northeast Lumber Manufacturers Association, which is trade association and grading agency for softwood lumber; the number 104 refers to the member mill, which is Stratton Lumber in the Rangeley area. The wood stamped CIFQ refers to Council of the Quebec Forest Industires and mill number 240 is Produit forestiers Resolu in Saint-Thomas-Didyme, Quebec. But all you really need to remember is that NeLMA is the trade association for Maine’s larger mills and many smaller ones. Therefore, choose NeLMA to support local sourcing. (For more on stamps, see “On reading lumber stamps” below.

Why should you even have to know how to read a grade stamp to support local mills? Why isn’t labeling better? The short answer is that most lumber is a commodity. A 2 x 4 from Maine performs about the same as a 2 x 4 from somewhere else. More on that later.

Also equally confounding is choosing lumber that supports sustainable forestry. (Neither of the 2 x 4s illustrated above carries any guarantee that the forestry that produced itis sustainable. It might be sustainable, it might not. You just don’t know.) The only guarantee is lumber with a green certification stamp. The two primary certifying organizations – the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) – audit the forest management and verify the tracking of each log from stump to sawmill

Photo by Lee Burnett

The wood above was bought at The Home Depot, which is supplied by JD Irving, the giant New Brunswick conglomerate, which also owns several sawmills in Maine. Note the Sustainable Forestry Initiative stamp, which is the only example I found of green-certified wood amid stacks of other lumber. If you’ve bought dimensional lumber at The Home Depot, you may have bought green certified wood without even realizing it. FSC lumber, which some consider a greener certification than SFI, is more difficult to find. Other retail lumber yards may carry it one month, but not the next and it’s never labeled. Why sell it and not label it? Again, it stems from the commodity nature of most lumber.

The backstory helps explain why green-certified wood is so invisible in lumberyards. Fifteen years ago, green certified lumber was going to be a big thing. Maine Governor John Baldacci pushed the state’s major landowners to get their woodlands certified. Major book and magazine publishers announced intentions to source from sustainably certified forests. Landowners spent big bucks to hire third-party auditing agencies (such as FSC and SFI) and secured certification of millions of acres. It was assumed that lumber customers would pay a little more for the certified label, just as food consumers are willing to pay a little more for the organic label. It didn’t happen. Certified wood failed to resonate with consumers and its visibility in the marketplace gradually declined to where it is today. Certified lumber is still available in lumber yards, but it’s hit or miss whether it will be there when you go.

For greater certainty about the source of your lumber, buy directly from one of Maine’s niche sawmills, which buy logs from close-to-home sources. Here you can find pine and hemlock timbers, cedar shingles and clapboards, tamarack decking and other lumber you won’t find in a big box store. The sources of wood can generally be described as sustainable, although it’s an approximation because the wood is a blend, with logs coming from a variety of woodland owners practicing varieties of forestry. (It’s impossible to know about individual logs without chain-of-custody tracking.) The blend comes from three basic tiers of forestry of increasing rigor. The bottom tier is legally harvested wood, as determined by Maine’s Forest Practices Act, which regulates against over-harvesting, silting up streams, destroying critical habitats and other abuses. The middle tier is wood coming from woodlands enrolled in the Tree Growth Tax program, where landowners receive a tax incentive for following a forest management plan. The upper tier, which is undocumented is wood harvested from woodlands were the landowners go beyond the minimum requirements of the Tree Growth Program and take greater effort to protect forest health, overall ecological values and/or carbon storage. This is the blend you buy when you buy from local mills.

It’s possible to support patient forestry without the guarantee of a green-certified label. Look for wide-plank pine - typically 12 to 20 inches in width and used primarily in traditional flooring and paneling. Wide-plank pine comes from trees that are the product of more than a single lifetime of stewardship. You can be confident they are not logged from old growth forests because virgin forests don’t exist in New England, except in scattered reserves protected from logging. You can be also be reasonably sure they are not the spoils of exploitive logging because timber is not allowed to grow very large under a short-term management regime. Typically, these trees are intentionally grown for a 100 years or more either through active or hands-off management.

Wide-plank flooring in a bed room Photo courtesy of The Wood Mill of Maine

For greatest certainty about the source of your wood, contract with a portable sawmill operator. It can save you some money, carries a low carbon footprint and is satisfying in self-reliant way. It’s more effort than most people are willing to take on, as it typically involves dealing with, not just a portable sawmiller, but a logger, trucker, and possibly a kiln owner.

The day is coming when buying lumber will be as transparent as buying from an online retailer. It’s being driven by carbon-storage value of wood and life cycle accounting. More and more, companies and trade associations are publishing Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) documenting the cradle-to-grave impact of their products.

Until then, below is a summary of buying suggestions.

Maine-grown dimensional lumber It’s readily available in retail lumber yards. Look for the NeLMA stamp.

Sustainably-grown dimensional lumber It’s available at Home Depot. Look for the SFI stamp

Pine finish boards, trim, pattern-siding, mouldings: Readily available in retail lumber yards. Look for the NeLMA stamp.

Wide-plank pine The Wood Mill of Maine and Robbins Lumber in Searsmont are sources with custom orders

Oriented-strand board Readily available in retail lumber yards. Huber Engineered Wood’s manufacturing plant in Aroostook County produces AdvanTech and ZipSystem from pressed aspen chips. OSB Siding – soon to be readily available from the Louisiana-Pacific facility on New Limerick, ME

Plywood Columbia Forest Products produces hardwood veneer at a manufacturing plant in Aroostook County.

Pressure-treated timbers Maine Wood Treaters in Mechanic Falls recently began producing pressure-treated Maine-grown red pine as a competitive substitute for the ubiquitous pressure-treated southern yellow pine. It’s available through most retail lumber yards in Maine, though it may be a specal order. (PT red pine is currently only available in timbers, not dimensional lumber.)

Pine and hemlock timbers, cedar shingles, decking, clapboards, pattern-siding, rough-sawn lumber Available through dozens of niche sawmills, planing mills and manufacturers. See Maine Wood Guide

On reading lumber stamps

Using the NeLMA wood at the top of the story, I’ll illustrate the five pieces of information conveyed by a stamp:

Species: S-P-F-s. This refers to spruce-pine-fir, a mix of species with similar structural characteristics. The small “s” refers to south, or wood grown in the US, as opposed to Canada

Grade: Stud

Moisture content: KD refers to kiln dried to a moisture content no higher than 19 percent

Certifying agency: NeLMA

Mill: Number 104, Stratton Lumber